.jpg)

A River Runs Through It

One of the most famous and beloved houses in the country has not survived without a struggle.

BY: Renee Valois

June 09, 2009

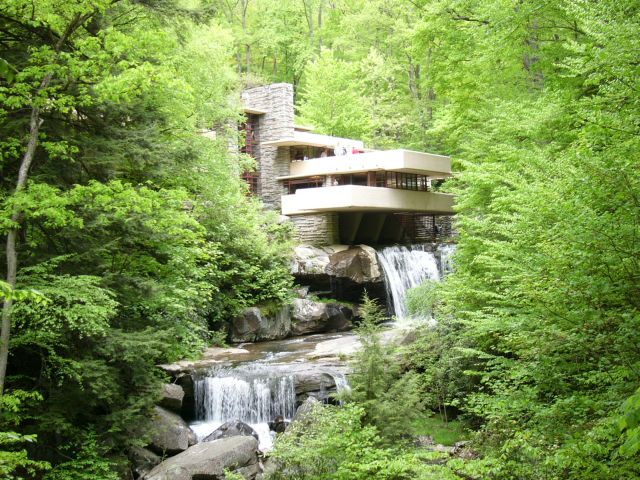

From the very beginning, Fallingwater made a huge splash in the world of architecture. In 2000 the American Institute of Architects voted it the Building of the Century. But Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous house did not always look like it would last through the century.

The house remains as unique today as when it was designed in 1935. But the very originality that made Fallingwater so beloved has also endangered it.

When department store magnate Edgar J. Kaufmann commissioned Wright to design a country house for him on the Bear Run stream on forested mountain property in western Pennsylvania, he expected Wright to build a retreat with a view of the waterfall his family loved. He did not anticipate a house built right on top of the river—incorporating the very boulders upon which the family enjoyed basking.

Legend has it that the design for Fallingwater spewed out of Wright in one frantic session. It started one morning in September 1935, when Kaufmann called Wright to inform him that he was in Milwaukee, about to drive up to Taliesin (Wright’s home and studio in his childhood town of Spring Green, Wis.) to see Wright’s designs. Kaufmann had been waiting impatiently for months. Wright replied “Come along, E.J. We’re ready for you,” implying that the plans were finished. In reality, Wright had not even begun to work on the designs—at least on paper.

As his apprentices Edgar Tafel and Bob Mosher later recalled, Wright talked to himself as he laid out plans for the house. “Liliane and E.J. will have tea on the balcony . . . The rock on which E.J. sits will be the hearth, coming right out of the floor, the fire burning just behind it . . .” He kept his two assistants sharpening the colored pencils he rapidly used up. The plans, elevations, and sections were finished just in time for Kaufmann’s arrival.

Fallingwater comprises a series of concrete levels anchored in rock. It is so integrated into the landscape that the huge boulder Wright envisioned actually protrudes through the floor of the living room. Multilevel platforms and balconies mimic the natural ledges of the falls, and stone quarried from the area enhances the organic look. The cantilevered house projects over the river, and steps from the living room lead right down to the water.

The spectacle of breathtaking architecture enfolded in a beautiful forest stream has drawn visitors from around the world. In 1963 Edgar Kaufmann Jr., who was instrumental in his father’s original decision to hire Wright, gave Fallingwater and its acreage to the public in care of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy as a memorial to his parents. Today, 135,000 people visit annually.

But peaceful surroundings belie the danger Fallingwater has endured through the decades. In 1956 a tornado hit, and Edgar Jr. wrote, “The house was being racked . . . The main stairs . . . carried a cascade from the hillside behind the house. Ankle deep in water, we looked over an alien lake obliterating the glen and shoving restlessly against glass doors, while the wind howled and the rain poured down in wild sheets . . . The next morning we awoke to a house thick with sludge. The banks of Bear Run were ravaged . . . smaller boulders were swept away, trees were down . . . Two bronze statues, set outdoors near the house, had disappeared.”

Fallingwater came through the terrible storm structurally intact, and the mud and drowned snakes were cleaned out, but nagging problems have resurfaced through the years.

When the house was built, many engineers feared the cantilevers that supported the floors would eventually collapse—or the river would cause the house to disintegrate. Indeed, the cantilevers sagged so much over time, and moisture damage was so pervasive, that in 1999 a plan was formulated to resolve both issues. In 2002 the cantilevers were stabilized with post-tensioning, using high-strength steel cables buried inside the floors.

Lynda Waggoner, director of Fallingwater, says water damage had warped doors, peeled paint, and caused stains and cracks in walls, creating problems that rivaled the sagging cantilevers in importance. Fortunately, advances in modern technology have made it possible to completely waterproof the building.

However, Waggoner says that, just as with any home, one might put a new roof on, but then something else needs to be replaced—there are always new issues. She says that although the original glass was replaced with UV-filtering laminate glass in 1987, it’s beginning to fail. Also, it has always been difficult to get paint to adhere to the building because Fallingwater has a lot of horizontal surfaces.

Waggoner says it’s difficult to ask fans of preservation for more money after the big capital campaign that recently funded the extensive structural and waterproofing work.

But the physical poetry of Fallingwater will surely ensure its preservation. As Waggoner says, “It’s one of our national treasures. It’s the most famous modern house museum on the planet. Few houses speak to a whole host of people. But you don’t have to be an architectural aficionado to love Fallingwater.”

Renee Valois wrote about Civil War battle relics in the September/October 2006 issue of the magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment