Tibetan Perspectives on Death and DyingTibetan Buddhism recognizes the natural fact that human beings tend to avoid admitting death as an immediate threat in their own lives. Indeed, this refusal to acknowledge the imminence of death and impermanence is regarded in Buddhism as a fundamental cause of the confusion and ignorance that prevents spiritual progress. Spiritual growth is achieved not by cowering from death, but by confronting it head on. Therefore, to facilitate confrontation with such raw reality, Buddhism offers several detailed meditative strategies. These death meditations enable Buddhist practitioners to engage seriously the truth of impermanence and, in turn, to comprehend the true nature of human existence. Mindfulness of death engenders both control and freedom; it brings about control in the sense of curbing the desire for permanence and security, and it promotes freedom by offering the meditator an enduring glimpse of the Buddha's liberating wisdom. The clear advantages of regularly contemplating impermanence and death make such meditations supreme among all the various types of Tibetan Buddhist mindfulness training. Taking the practice seriously helps to inspire further spiritual endeavor, overcome the delusions of permanence and immortality, and increase the probability of a virtuous life?and death?experience.

In the religious traditions of Tibet it is taught that the first moment of death is marked by a gradual process of disintegration, in which both the mental and physical components of the dying individual begin to collapse. Lacking a physical support, the person's consciousness withdraws inward and gathers at the center of the heart before finally departing the body. Corresponding to the gradual deterioration of consciousness during death, the dying patient experiences a variety of distinctive visions, each marking a stage in the dying process. Meditators study these stages in order to gain intimate knowledge of them, since it is believed that a person familiar with the death experience is less likely to be frightened when death finally arrives. But more importantly, a detailed knowledge of the dying process enables advanced practitioners to simulate the experience during meditation, thereby gaining control over the actual process. Cultivation and control of these subtle visionary states of consciousness function to transform the meditator's mind and body into the divine form of a fully liberated awakened being, a Buddha.

Before the ordinary dying process is complete, relatives and friends are advised to quietly bid the dying person farewell, without creating an overly dramatic situation. Tibetans believe that it is crucial for both the dying person and those around him or her to avoid causing excessive regret or longing in the patient, but instead to foster virtuous states of mind. The state of mind at the time of death is believed to influence directly the momentum of the departing consciousness. Any thoughts that occur during this time are extremely potent; it is therefore significant for the individual to generate and sustain a positive mental state thoughout all the stages of dying. In other words, the quality of mind at the time of death is a critical component in determining the dying person's future destiny. If disruptive thoughts can be avoided while simultaneously directing the mind toward pure and virtuous thoughts, the ordinary person may be capable of positively controlling the outcome of the dying event. To help the patient achieve this goal, a spiritual master, or lama (bla ma), may whisper guiding instructions into the person's ear. Traditionally, these instructions are read from a variety of ritual texts designed to help guide the deceased's consciousness through the intermediate realm between lives, known in Tibetan as bardo.

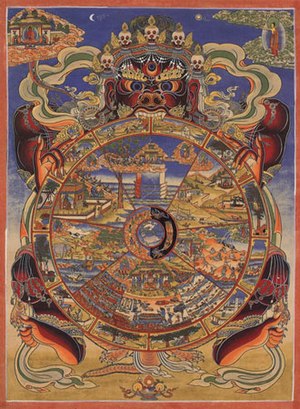

Tibetan Buddhism recognizes four stages in the life cycle of a sentient being: birth, the period between birth and death, death, and the period between death and the next birth, or bardo. The postmortem bardo journey is said to last no longer than seven weeks (49 days). By the end of the forty-ninth day the deceased is reborn into a worldly state influenced by his or her past actions, collectively referred to in Buddhism as karma. The principle of karma is essentially the simple law of cause and effect, whereby it is held that the moral quality of an individual's actions performed previously determines the quality of experience in the future?in this case, the person's next life. The bardo state is recognized as an opportunity for change, a starting point of transformation. It is understood as a gap between familiar boundaries through which is gained a glimpse of the true nature of Reality. By fully recognizing this ultimate nature, the deceased is capable of breaking the afflictive cycle of rebirth (samsara) and achieving final liberation, Buddhahood. Much of an advanced practitioner's meditative training is designed to meet this transformative moment, but in most ordinary cases, the deceased is dependent upon the assistance of the lama, who recites the guiding instructions from the bardo literature in order to bring Reality into clear focus. The words of the lama communicate the essential truth underlying the postmortem experience, giving the deceased an ultimate point of reference to make sense of the often confusing and terrifying visions that are confronted during the bardo period. Moreover, recitation of the texts within a ceremonial setting offers practical wisdom to the participants in the ritual drama. The benefits of the texts can thus be understood at two levels: through recitation and explication of the texts' meaning, the deceased is reminded of knowledge previously learned and experienced in life, while at the same time, family members and friends receive spiritual teachings that will improve and enrich their present lives. In this way, the bardo literature offers not only a method of guidance, but also a varied program for an array of performance styles, involving liturgy, ritual offering, prayer, and scripture recitation, all operating as an integrated whole to insure a positive destiny for the living and the dead.